-

Shop All

-

Ration Packs

-

Special Diets

-

Snacks, Drinks & Accessories

- About Us

Matthias Ekman - A Solo Traverse of the Himalayan High Route

October 05, 2022

Expedition Foods (EF): Tell us a little about yourself: Who are you? Where are you from?

Matthias Ekman (ME): My name is Matthias Ekman, I am an ultra-runner, photographer and neuroscientist. I was born in Germany, but I am based in the Netherlands for the past 11 years — from the flatlands to the Himalayas. Traversing the Himalayas was not my first “mountain project”, but by far the longest. In 2017, I did a winter traverse through the High Sierra and in 2018 I ran 850 km along the Pyrenean Haute Route in 22 days. I am very much drawn to mountainous terrain where the route is not always obvious, and sometimes you just have to make up your own.

EF: Tell us about your expedition, where did you go?

ME: A few years back I read an internet post where alpinists discussed the safest crossing of a 5000m mountain pass in the far west of Nepal. One team just got back and said it was impossible, too dangerous. Another team had to be rescued by helicopter as they run out of food after getting lost in the steep valleys leading up to the pass. It turned out that they were all basically following the wrong valley up to the wrong mountain. To me that was fascinating and daunting at the same time - with all the technology today, it was still possible to get really lost.

Later I learned that this mountain pass was part of a high route traversing the Himalayas called the Great Himalayan Trail (GHT). Long story short, in April of 2022, I found myself at the starting point of this trek. The route starts at the eastern border in Nepal at Kanchenjunga Base Camp (getting there is already an adventure in itself) and ends at the Tibetan/Chinese border in Hilsa in the west. Along the way I crossed 24 mountain passes above 5000m with the highest point at 6200m at Sherpani Col. The traverse is extremely diverse, you walk through deep snow and cross glaciers, but also bushwhack through dense forest areas and finally cross a completely dry, dessert-like plateau before reaching the Tibetan border. Around half the time I camped out in my tent and the remaining days I stayed with local people in their homes or in lodges. In total I covered a distance of about 1800 km, but it is one of these journeys where mileage does not say much, as one day you travel on well-worn trails and on the next day there is no trail at all and instead you spend hours climbing from boulder to boulder. The entire journey took me about 100 days and I lost 10% of my body weight.

EF: What did you enjoy the most about the Himalayan High Route?

ME: There are a few sections in the far East and the far West that are extremely remote, where I went for weeks without seeing anyone. Going solo and being completely self-reliant makes this a very special and intense experience. In your normal life, when was the last time you were really alone… and for how long was that? In his situation you really learn to trust yourself as there is no one around to ask for help or to blame for your bad decisions or moods. This can be confronting, but also very insightful. Finding yourself in such a remote landscape, camping in the snow, high up in the Himalayan mountains really sharpens your senses and brings a clarity of thought that is hard to describe.

While drawing immense value from being by myself for so long, I also enjoyed the interactions with local people a lot. I was really taken by the kindness of locals. I brought food and supplies for about half of my journey, meaning that I was completely reliant on local communities for the other half. Back in the Netherlands it would never occur to me to walk to someone’s home and ask if I can sleep and eat at their place, but in Nepal this became very normal very quickly. Locals were very curious about where I was from, what kind of foods I eat and how many children I have.

EF: What did you find most challenging?

ME: Paradoxical as it may sound, I found it very challenging to pass through the more touristy areas, like the Everest and Annapurna regions. Being immersed in a different culture for so long, gives you a different perspective and I could not help but feeling more and more critical of my own culture, sometimes even a bit ashamed of it. I often wondered, what do Nepalis really think about us westerners. There was this one situation when someone shouted at their Nepali guide because their porridge had too much sugar in it, or because the internet in the lodge was not working.

Another challenging aspect was the weather. Due to the climate in the Himalayas, there is actually only a small window of ideal hiking weather. Basically, two months in spring and two months in the fall. Around that weather window it is either winter or monsoon season. For such a long journey that means you find yourself in severe weather most of the time. I don’t mind rain and I actually like the cold, but with the start of the monsoon, it also means that leeches come out — in thousands. It is something you have to experience for yourself in order to know how difficult it is. In the beginning I thought I could still avoid being bitten, by stopping a lot, taking off my shoes and removing all the leeches that found their way onto my skin. But soon it became clear that this was an impossible task, whenever I stopped to remove 5 leeches from one shoe, 10 more found their way into my other shoe. After a few days of battling the blood suckers and rushing through forests without stopping, I felt exhausted, gave up and just accepted that this is what it is. Some of my clothes still have blood stains and I doubt they will ever get clean again.

EF: How did you train for such an epic journey?

ME: Training for the Himalayas is an interesting project in itself, when the highest mountain nearby is only 72m high. Still, when thinking about possible reasons why my project could fail, I was mostly concerned about getting lost, running out of food, severe weather, gear failure or permit issues, not so much about my personal fitness. Having said that, I did have some concerns about the heavy pack and staying healthy over such a long journey. I addressed these worries by carrying my loaded backpack a lot and doing some heavy weight lifting. I thought that my body will eventually get used to the 28 kg backpack one way or another, but starting 6 months out, will also make the journey much more enjoyable. Still, this was not an ultra-run, where I would collapse every night in my tent not knowing how I could possibly start the next day. Instead, the journey would involve getting slowly acclimatized to the altitude and often reaching the foot of a mountain pass in the afternoon, too late to still cross on the same day. Therefore, a lot of days were rather short and allowed my body to recover.

I had talked to Robin Boustead, the founder of the Great Himalayan Trail, before I left and when I mentioned to him that I had only 120 days in total he was sure that this would not be possible in such a short time. I think Robin is right to stress that this is a different trail and people should not take it lightly, but after about a month in the Himalayas I knew that I had enough time. In that sense I was much more relaxed when it came to training the physical side compared to other running projects I did in the past. I did, however, gather as much information as possible about possible routes and potential navigation issues. I also started climbing again and made sure I was familiar with my gear, practiced abseiling and pitching my tent with big gloves on.

EF: What did you eat? How did you prepare your food?

ME: I wanted to rely on local food as much as possible as this is a great way to support the local communities. So, when staying with people in their homes that meant rice, potatoes, lentils - the famous Dhal Bat dish. Sometimes I would come by some Yak herders and they would offer me some rice or Tibetan tea (black tea with salt and butter). In lower elevations I could sometimes ask for eggs, vegetables, or fruit like banana and mango, but these were very rare to come by. At home we are so used to having all kinds of fruits and vegetables available all year around. In Nepal, when I asked about apples, people would often just shrug and laugh… everyone knows that apple season only starts in the early fall. Especially in the higher elevation areas locals rely a lot on sugar to cover their energy intake. I always found it astounding that the Sherpa communities do not eat breakfast, until I saw the amount of sugar they add to their morning tea. Biscuits (Nepali call them “biscooots”) and instant noodles (“Wei-wei”) are widely available and locals would often sell them for a few rupees.

For the days that I was completely self-reliant, I carried oats, nuts and dried fruits for breakfast and lunch and had my big meal, the Expedition Foods 1000 kcal pouch for dinner. I would carry a gas stove to boil water or melt snow. Since there was a limit on how much weight I could carry and with 700g of food per day (~3200 kcal) you basically walk hungry all the time. On previous journeys I managed to get by with far less kcal per day, but being at high altitude in the cold, your body consumes so much more, even when just resting.

Having the big meal in the evening works well for me personally. I find it easier to feel hungry during the day and having the big meal in the evening helps me to feel satiated and sleep to recover well during the night. For shorter adventures I always thought that calories are calories and didn’t worry too much about the distribution of macronutrients. However, for these 100+ days I was worried that especially the lack of protein in my diet would be hard on my body over time.

When I first started looking at the Expedition Foods offerings, I was surprised to learn that the dishes vary a lot in their composition of calories. For instance, the Chicken, Parmesan and Basil Risotto has almost twice as much protein as other dishes. Same holds for the weight of the dishes, they are all the same in terms of calories of course, but some flavours are 50g lighter than others. That does not sound like much, but if you carry 10 of them it adds up. Further, some dishes require up to 150ml more water than others. More hot water, means more gas, means more weight to carry. Of course, these things don’t matter for every expedition, but when going solo and carrying everything by yourself, they do. In the end I actually wrote a computer algorithm that picked the optimal dishes based on these three parameters… but maybe that went a bit too far and people should just choose the dishes they like (laughs). I ended up liking the Chicken, Parmesan and Basil Risotto a lot and that was also one of the algorithm’s favorite.

EF: What were your 5 favourite items that you had with you?

ME: The honest answer is that except for my photo camera, I didn’t bring anything that I didn’t need. When it was raining, my rain jacket was my favourite item. When it was cold at night, my sleeping bag was my favourite item… I was contemplating for a long time whether or not to bring a professional camera with me. In the end I am glad that I did. It made me stop and appreciate things more often than I would usually do and I get immense joy from looking back at some of the memories I captured with it.

EF: Was there anything that you decided you shouldn't have taken or wouldn't take again?

ME: Since the route is so varied - one day you cross rivers, another day you abseil from a glacier - everything you bring in terms of gear is a compromise. For instance, having a 4-season tent would be ideal for the high passes, but way too warm and heavy for the hot and humid dessert-like sections in the west. Similarly, proper crampons really help when climbing the ice-covered rock over Amphu Labsta, but you won’t need them 95% of the time and just carry dead weight. For that reason, I find it extremely difficult to give advice on gear as every season in the Himalayas is different. For instance, weatherwise 2022 was a very special year as we saw a record level of snow during the winter, with snow levels remaining very high throughout April and at the same time we had an early start of the monsoon season already at the end of May. Of course, like everyone else, I like to go minimal and light, but for the Himalayan traverse I really used everything that was in my backpack.

EF: Do you have any words of advice for other mountaineers aiming for the Himalayan High Route?

ME: One thing I wish I had known before is how rapidly the Himalayas are changing. New dirt roads are built at a record pace often burying the old trail underneath. In total I walked on roughly 400 km of dirt road, often still catching the excavator in action. From a local perspective it is difficult to argue against new roads, as it comes with better access to schools, hospitals and cheaper foods. Personally, I am worried about what it will mean for the Himalayan High Route in the long term. Years ago, there was also a Himalayan Low Route that has been long swallowed by the growth of urban areas. Will the High Route face the same problem at some point? I hope not and I think it is up to future hikers and mountaineers to try and establish new route variations that preserve the remote and rugged spirit of the GHT.

EF: What's next for you? Are there any future expeditions in the pipeline?

ME: The dreaded “what’s next” question, while I have yet to wash my sleeping bag (laughs). Honestly, during the last weeks of my journey I developed a deep longing for feeling “home” somewhere. More stability than the Van I am currently living in while working as a guide in the Italian alps. Once I figure that out, my mind will start thinking about new projects. Actually, there are incredibly beautiful mountains in the far west of Nepal that no one (in the West) has even heard about. Some still unclimbed…

Also in Stories

Fuelling a Marathon des Sables Win: Anna Comet Pascua x Expedition Foods

January 27, 2026

Discover how a Marathon des Sables champion fuelled her victory with Expedition Foods. In this in‑depth interview, she shares her nutrition strategy, favourite freeze‑dried meals, calorie planning, and insights into multi‑day racing and motherhood.

Eat, Paddle, Sleep, Repeat: Life on the Yukon 1000

November 06, 2025

Firsthand account of completing the Yukon 1000 in 7 days; what we ate, packed, and learned about food, sleep, and self‑reliance on the river.

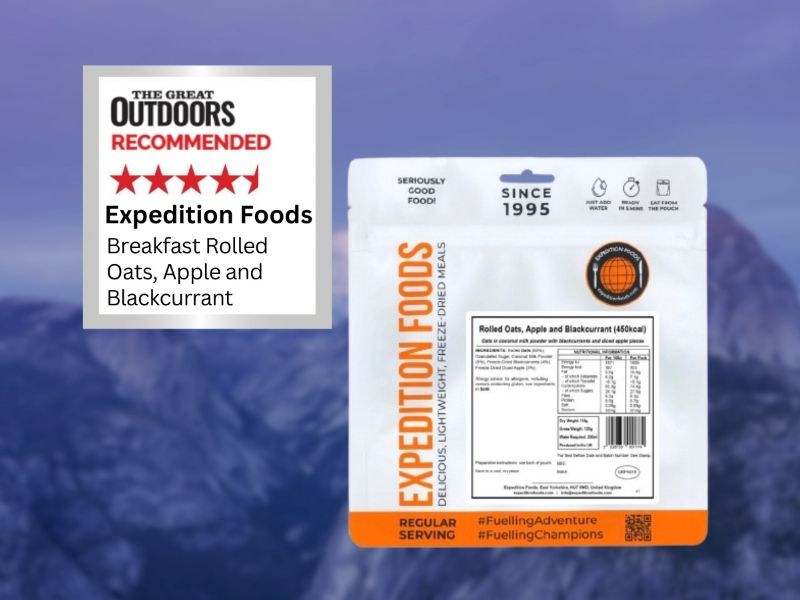

Expedition Foods Breakfast Earns Praise from The Great Outdoors Magazine!

September 29, 2025

We’re proud to have received a glowing review for our plant-based breakfast, Rolled Oats with Apple and Blackcurrant, that’s not only nutritious and delicious but also mindful of dietary needs and environmental impact.