-

Shop All

-

Ration Packs

-

Special Diets

-

Snacks, Drinks & Accessories

- About Us

Will Copestake's Circumnavigation of Scotland by Kayak

April 17, 2020

Words and Photography by Will Copestake

This article first appeared in BASE magazine issue 02. For the latest from BASE including the latest digital issue in full direct to your inbox, be sure to subscribe for free.

Once on the tide, you can’t turn back, whispered a voice in my head. It was frighteningly persistent, and I felt sick.

Eighty days into a solo sea kayaking expedition around Scotland, I had reached Cape Wrath - the most northwesterly point on mainland Britain on the north coast of Scotland. ‘The turning point’ as the Vikings named it and the gateway to an infamously rough and committing stretch of paddling. I had safely landed in a small cove and settled into a bothy to spend the night. Wandering to the top of a nearby cliff I had hoped to inspect what lay ahead and build confidence for what I might experience over the coming days.

Looking east along a line of headlands, I felt my stomach churn as I watched huge waves breaking over tidal races. The flow was faster than I could paddle against. I knew it would be different at slack tide, but I couldn’t shake the thought of being tossed amongst the conditions I saw. A voice in my head had started to whisper fear, and fear quickly turned to self doubt. Over the last 800 kilometres, I had grown used to tidal planning and executing each day to make best use of their flow or lack thereof. I had ready advice available from friends just a quick phone call away, but out here, on this remote cliff, I felt so very much alone. Once on the water it would be just me, my kayak, and an ocean moving swiftly east. There was something frightening about the total commitment of the north coast; the fierce reputation of this place had built up in my head over the last few months, which made it seem worse than what I had paddled so far.

Below my feet, the cracks and booms of waves against rock thundered through a chatter of seabirds nesting on their precipitous perches below. Like those birds, I felt I was teetering on a thin ledge between safe land and dangerous sea. In reality my success or failure lay squarely in my planning for the tides and winds which I had already become so well accustomed to doing. But the voice whispered again in my ear, once on the tide you can’t turn back.

There is a delicate balance between a sense of fear and willingness to commit in any walk of life, be it a businessman investing in his stocks, an arachnophobe picking up a spider from the kitchen floor, or a sea kayaker navigating a tidal headland. In every case there is that little voice in our heads that cries hesitation. But therein lies the allure of adventure which is to overcome that thought just to see what happens. You might arrive around a headland triumphant or you might throw that spider across the room with a childish scream, if you don’t try you will never know.

In a paddling sense, I had experienced this voice of doubt before Cape Wrath, mostly on offshore open passages. I found the call starts in the back of my mind after an hour or two paddling away from land, from where it grows louder and louder. In such times, the temptation to listen was always alluring even when I was experiencing calm and manageable seas. If I turned back for the weather then that was a choice well made, but retreat for no good reason other than a beckoning doubt brought instant regret once home. To push past the voice with observation and rational reasoning always led to a tremendous sense of reward at overcoming it. This was how I would treat the north coast, headland by headland, with good preparation and by managing the difference between irrational fear and rational awareness.

Looking down, I could see the eastward stream pulling full bore through a narrow gap. Between mighty cliff and rocky island, the sea curled over in a chaotic spray as the flow broke into white horses. I felt sick just looking at it. The thought of entering that chop churned my stomach in flips and leaps just as tumultuous as what I was looking at. It kept me awake most of the night. As the next day arrived and the tides were slack, I checked conditions were good - which they were - sucked up my nerves and pushed out to sea. Anxiously rounding the corner, I entered the waves that had stirred up so much fear and doubt from the shore. Indeed it was rough, and required hard paddling to execute success, but to my surprise the reality of the race wasn’t fear but fun. I passed the cliffs with a smile on my face, and with all self doubt removed in the process.

Over the next week I slowly pushed across the north coast one headland at a time with the same repeating routine of primal fear ashore and paddling enjoyment on the sea. On land, safe and dry, my mind was burdened with nerves each night, but on the water the next day they were washed away with the immediate purpose of the journey at hand.

The voice whispered again in my ear: once on the tide you can’t turn back

After several successful headlands rounded, I started to ignore the voices of fear. Complacently letting my planning slip this led to my most epic and challenging experience during my entire circumnavigation of Scotland as I rounded Holbourne Head. My second last headland in the north, it was the one day of my trip where the conditions became what I had feared, and that fear became a reality. This was the day on which I should have listened more carefully to the whispers of doubt.

A huge double-overhead swell had risen against the tide and a high wind forecast rose the waves steep enough to easily take my entire kayak bow to stern on their face. The new confidence of having aced the last few days without issue now turned to desperation, as I found myself fighting for survival for several hours. I remember the moment a wave actually barrelled over me, surfing me sideways as I braced hard, white knuckles piled into the breaking foam. I remember too the crack of waves erupting against the cliffs of an inescapable shore. I remember a horrible sense of being totally stationary as each crucial paddle placement wallowed in the waves. Every minute felt an hour and every stroke an effort to stay upright; my kayak was sinking and I was running out of energy. When I finally reached safe harbour, I was so exhausted that I needed help from a stranger to lift my kayak from the slipway. My cockpit was twelve inches deep in water from a leaking deck and I was shivering hard from the cold water and sheer adrenaline. I was physically and emotionally spent.

My mistake was reversing the routine; I had ignored the whispers of fear which had led to a lack of proper precautionary planning. Whilst, perhaps surprisingly, the fear during the event had been shelved in an effort to escape, afterwards it utterly consumed me.

In reflection, the experience had been terrifying. It was the closest I have come, before or since, to having a serious beatdown on the sea and for days after it affected me deeply with a reluctance to return to the water. A valuable lesson perhaps, experience as always came just after I needed it.

Those voices can sometimes turn from a hinderance to a useful tool. I have long said that the safest paddlers are the timid ones, but it is perhaps better to consider that a safe paddler recognises risk and listens to it by matching their planning to their ability. By acknowledging ‘the whispers’, rather than fear them, a greater picture of the journey ahead and its possible outcomes can be made, knowing when it is appropriate to listen or ignore them is then down to experience.

Since completing my solo circumnavigation of Scotland I have been privileged to turn adventure into a career as a kayak guide. Like my adventure, which began with relatively little experience in sea kayaking, I learnt to guide in a rather unconventional way. I was hired on the merit of that Scotland trip to an expedition guiding outfit in Chilean Patagonia where I was regularly sent into seriously remote locations in 45 knot headwinds with large groups of novice paddlers. Needless to say that first season was ‘educational’ and took swift and effective decision making to an extreme with lots of dynamic choices involved. At the time I had no formal training ( which I have now progressed through in subsequent years ) on how to kayak guide, and I only had the qualification of strong personal experience. I quickly learnt that guiding and strong personal paddling were two very different skills, although there were some overlapping elements.

I could see the eastward stream pulling full bore through a narrow gap. The sea curled over in a chaotic spray of white horses: I felt sick just looking at it.

The technical skills of Patagonian guiding involved a lot more towing and instruction than I was perhaps used to. In order to achieve a ‘safety first - safety second’ decision process, my most useful tool was the one I had learnt through expeditions, which I translated into my guiding format. I had to constantly listen to the ‘whispers’ as I’d discovered along the north coast of Scotland. By asking ‘what if’ at every turn or decision, incidents could be avoided proactively with enjoyment. To ignore the instincts meant picking up capsizes and reactively rescuing people.

Whether I’m leading trips in Scotland through my company Kayak Summer Isles, or on a major expedition in deepest Patagonia, I now maintain that listening ear to the whispers in my head. This approach, I think, might just make sense to a safe and experienced paddler. Rather than being the first sign of madness from too long on the sea, staying in tune with the inner voice of your consciousness is a sound practice for any major adventure.

This article first appeared in BASE magazine issue 02. For the latest from BASE including the latest digital issue in full direct to your inbox, be sure to subscribe for free.

Also in Stories

Fuelling a Marathon des Sables Win: Anna Comet Pascua x Expedition Foods

January 27, 2026

Discover how a Marathon des Sables champion fuelled her victory with Expedition Foods. In this in‑depth interview, she shares her nutrition strategy, favourite freeze‑dried meals, calorie planning, and insights into multi‑day racing and motherhood.

Eat, Paddle, Sleep, Repeat: Life on the Yukon 1000

November 06, 2025

Firsthand account of completing the Yukon 1000 in 7 days; what we ate, packed, and learned about food, sleep, and self‑reliance on the river.

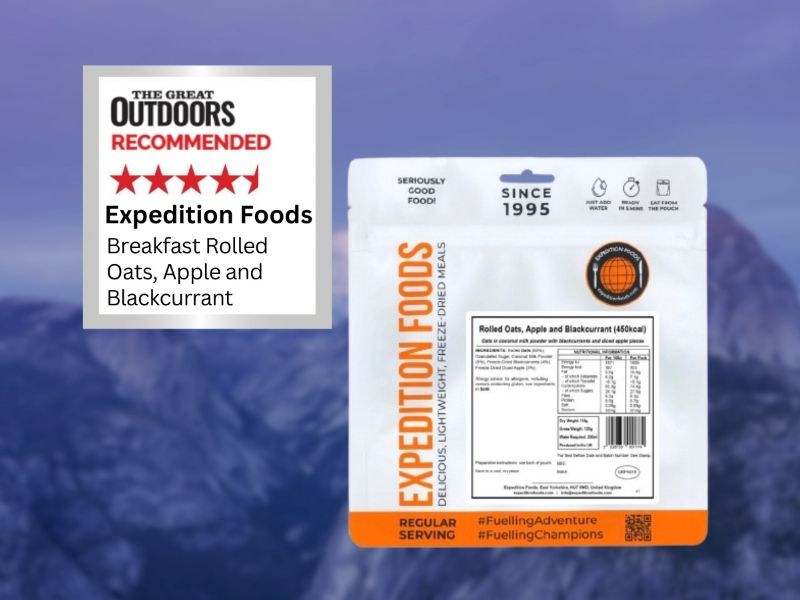

Expedition Foods Breakfast Earns Praise from The Great Outdoors Magazine!

September 29, 2025

We’re proud to have received a glowing review for our plant-based breakfast, Rolled Oats with Apple and Blackcurrant, that’s not only nutritious and delicious but also mindful of dietary needs and environmental impact.